For ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) or Civil Rights Title VI accommodations, translation/interpretation services, or more information call 503-731-4128, TTY 800-735-2900 or Oregon Relay Service 7-1-1. Si desea obtener información sobre este proyecto traducida al español, sírvase llamar al 503-731-4128.

Stations

Transportation and housing have significant, interrelated impacts on Oregonians’ quality of life. Transportation and housing comprise the two largest expenses for a typical household. Policy choices can impact environmental and physical health outcomes; mobility, economic, educational, and cultural opportunities; and the financial well-being of households.

Last year the Oregon State Legislature requested that ODOT examine policies and actions that could improve quality of life through increasing housing options with easy connections to transit. This aligns with our strategic goals to address equity, address climate change, improve access to public and active transportation, and address congestion.

While housing policy is not directly a part of ODOT’s mission, we are pursuing this Study due to the important connection between transportation and housing on the quality of life for all Oregonians, especially those traditionally underserved. The information we uncovered can help ODOT, other state agencies, public transportation providers, and regional, local, and tribal transportation and land use agencies better enable links between transit and housing of all types.

Click on the icons below to learn more about the research.

A housing primer was developed to provide a foundation for how housing markets function, how market failures arise, the roles of different market players, the housing development process, and typical funding considerations. It is intended to help ODOT, local transportation agencies, local governments, tribal nations, and community partners evaluate investments and policies as they consider the connections between transportation, land use, and housing.

Housing Supply and Demand

Housing markets are subject to the laws of supply and demand, though they are greatly influenced by government interventions. The demand for housing reflects the number of households with preferences for a given housing type (e.g., detached single-family, apartment), location, and price. Housing type preferences are unique to individual households that balance tradeoffs related to costs, incomes, features (e.g., bedrooms and bathrooms), design, and neighborhood amenities. Demand can be affected by changes in the desirability of an area, population, or the incomes of people seeking housing.

Housing supply consists of all housing units that exist and new units that are built. The private sector produces most new housing, and the market is governed by economic fundamentals of supply and demand, which are influenced by government regulation. Housing development relies on inputs set by numerous interrelated markets and players. Each input to development functions in its own market with supply and demand factors constantly in flux.

New Housing Development

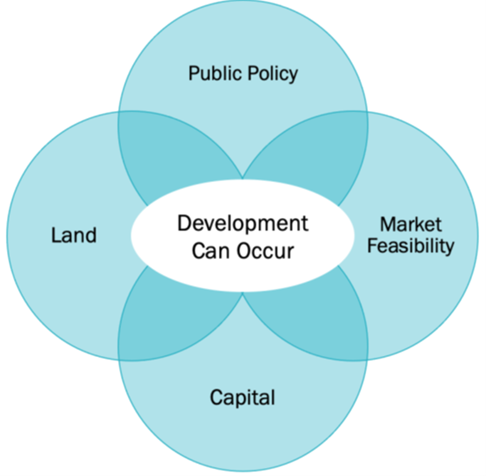

Housing development is a multi-stage, multi-year process without a certain outcome. For development to occur, several factors must align.

- Public policies, like land use restrictions or zoning, dictate what types of development can occur and where. Adding new policies and removing existing regulations is a complex process with interactions and impacts across many sectors.

- On a parcel of land, landowners and property developers evaluate a site for the economically highest and best use allowed by zoning, be that office, residential, commercial, or vacant land, depending on the parcel’s unique characteristics.

- Market feasibility is a robust process that assesses the demand for development – comparing the expected revenues against the investment costs (e.g., labor and materials) – for the desired types of development. Feasibility requires the development value to be greater than its costs; when the development value is less than the development costs, interventions are necessary to increase the value and/or reduce the costs. Otherwise, the project will not move forward.

- Capital is necessary to pay for the costs of development, and influences market feasibility through the financing terms set by the lender and expected investor returns. When real estate development cannot meet return requirements, return-seeking capital will flow to other sectors such as stocks and bonds.

The development of affordable (rent or income-restricted) housing has added complexity because the rents or purchase prices needed to be affordable to the intended tenants are below what it costs to develop. This “funding gap” requires public subsidy or free or low-cost funding which are typically provided via competitive annual funding programs from federal, state, or local agencies. This slows development and makes it more expensive (e.g., paying for lawyers and staff to complete applications for funding).

How Housing Markets Fail

Markets fail when they inefficiently allocate resources. In the case of housing markets, available housing units (the supply) cannot be accessed by households that can afford them and prefer them (the demand). Historically, when housing markets fail, the populations affected the most have been people with lower incomes, people who are minoritized, or otherwise marginalized households. In addition, when markets fail they cannot fix themselves. Interventions to correct a market failure typically come from the government, philanthropy, or non-profit sectors. Markets can also fail when the collective willingness to pay (market demand) is insufficient to influence the production of enough units compared to the number of households living in a market.

Conclusion

Housing market dynamics are complex and fluid, with many factors out of policymakers’ control. Changes in demand and supply, movement in materials and labor markets that interact with each other and with development costs, and changes in housing preferences all affect the quantity, nature, and location of housing units demanded and supplied. Whether and where new units get built depend on physical constraints related to the land and regulations governing its use, and the costs of production.

Despite this complexity, coordinated government policy action and investment can strongly influence the nature and location of housing that is built. Special consideration should be given to how policy decisions and investments will help achieve (or hinder) public goals like housing affordability, avoiding displacement, economic mobility, and greenhouse gas reduction, to name a few.

Understanding how housing markets function and fail, who the key players are, how they make decisions, and how governments can intervene to improve outcomes will help strengthen links between transportation, transit investments, and housing markets and development feasibility. Collaboration between housing and transit stakeholders during the early planning/development stages could assist with making more strategic decisions and deploying investments to improve community outcomes in the availability and affordability of housing choice and transportation efficiency.

To learn more about these topics, see the handy Housing Market Primer.

The literature review explored the existing research on the relationship between locating transit-supportive housing near transit routes and stations and the related role of first mile/last mile transit connections. Fourteen prominent research studies were examined to determine the effectiveness of current methods being used to create transit-supportive housing in communities.

The literature review focused on the following areas:

- Policies, practices, strategies, and/or barriers to the co-location of transit service, first mile/last mile connections, and housing - these were examined for applicability for different sized urban and rural communities and at the state level

- Addressing the needs of low-income households and the potential for gentrification

- The role of access to transit and first mile/last mile connections

- Potential barriers to transit-supportive development

- Equity implications

The literature review identified the following key findings for consideration as state and local governments, agencies, tribes, and transit providers develop policies and strategies to help provide connections between transit and quality affordable housing, including:

- Housing located within transit-oriented developments is more expensive. Due to the attractive nature of transit-oriented developments (amenities, proximity to jobs and services, and/or access to other transportation options), housing in these developments is often high quality and in high demand, leading to higher prices. The higher prices, however, may be offset from the lower transportation costs leading a potential net gain in overall affordability for households. When planning for housing in transit-oriented developments, ODOT and its partners could factor in transportation savings to determine if there is a net gain before identifying the number or magnitude of additional programs to increase housing access for low-income individuals.

- Transit ridership is often influenced more by the quality of the service than the areas it serves. Frequent and premium transit services can attract riders even when the stops and surrounding environment are less inviting. However, very successful transit needs to be part of a well-connected network with amenities, sidewalks, and first mile/last mile connections to minimize barriers to transit access. Land use variables, such as housing and job density, complement transit service by creating a conducive environment and providing a ridership base that can better support higher frequencies and premium transit services.

- When designing new routes, evaluating changes to existing routes, or implementing a system redesign, it is important to evaluate accessibility changes to jobs and services for low-income and underserved residents. This involves determining the location of jobs and services in relation to transit routes; measuring travel time changes for low-income residents, affordable housing communities, and other underserved areas; and including agencies that represent these communities in the planning process. These efforts should help to preserve access for the groups and not leave them out of the conversation when transit investments are made.

- Policies that disincentivize personal automobiles can harm low-income individuals. While increased gas taxes, congestion fees, parking restrictions, and other policies may be effective in decreasing personal automobile usage, a corresponding improvement in transit service and the availability of other transportation options is needed to avoid increasing transportation costs for low-income households.

- Transit investments create the potential for gentrification and resulting displacement. This potential needs to be anticipated and addressed during the planning process.

- Integrated transportation and land use planning between agencies, transit providers, and local jurisdictions is important to achieving transit-supportive housing. Coordination around zoning; transportation and transit planning; development review; and ongoing monitoring can help break down the compartmentalization of transit and land use/housing decisions.

- First mile/last mile and the urban form matters. Convenient and safe multimodal connections between transit, housing, and land use density create conditions for transit and housing integration.

To learn more about the Literature Review, click here.

A statewide policy review was performed to better understand the relationship between transit, housing, and land use policies and how these policies affect community quality of life. This review was completed in 2021 and therefore looked at state policies as of 2020 and 2021; a variety of changes have been made in policy since then, but this review still provides a foundation for considering their impact on transit and housing linkages. The following key takeaways from the policy review illustrate current transit and housing conditions in Oregon.

- A clear definition and statewide policy position related to “transit-supportive housing” is needed to encourage its development. This concept is not currently well-defined or directly addressed. Many documents are generally supportive or do not prohibit transit-supportive housing but do not specifically encourage it. A consistently applied policy could improve housing production and affordability, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, etc. – and direct funding and investment toward these goals.

- Coordination between state agencies and local and regional partners is key in addressing and delivering transit-supportive housing. Land use, housing, and transit, while addressed within local community comprehensive plans, are aspects of the built environment that are often affected independently by separate state agencies. Greater coordination and collaboration between the agencies may ultimately benefit Oregon communities.

- There are opportunities to leverage recent legislative, executive, and agency actions to further transit-supportive housing policies. House Bills 2001 and 2003 (both passed in 2019) focus on missing middle housing and statewide housing needs, respectively. They will change how housing needs are met and, over time, how residential densities are distributed in many of Oregon’s communities. Executive Orders 20-04 and 17-20 are focused on climate action and greenhouse gas emissions, establishing emissions targets, emissions reductions, and climate-related performance measures for both affordable housing and transportation projects. ODOT’s Strategic Action Plan creates a new vision and new priorities for the organization. Combined, these actions create space to find opportunities to establish transit-supportive housing policies that address a combination of these initiatives within multiple state-level agencies.

- Transit-supportive housing performance measures, evaluation criteria, and guidance would benefit any transit-supportive housing policy. If transit-supported housing becomes a policy focus, implementation will benefit from being better able to assess outcomes, track goals, and refine strategies promoting it.

To learn more about the Statewide Policy review, click here.

Click on the icons below to learn more about the results.

Case studies include original research, discussions with key individuals, and data from existing written sources to provide a comprehensive overview of the successes and lessons learned from transit-supportive housing projects both within and outside of Oregon.

The following highlights some of the key lessons learned from the Oregon case studies:

- A realistic understanding of actual housing needs, as provided by a housing needs analysis, can help eliminate misconceptions and direct efforts to the right targets.

- Coordination between land use and transit planning is key to successful developments and transit routes.

- Understanding market forces is important when undertaking regulatory changes as not everything that can be built will be built.

- Undertaking regulatory revisions concurrently with a master planning process can help the two processes inform each other.

- Reducing or eliminating parking requirements near transit can reduce the cost of development and incentivize transit use.

- A clear and objective approval process can make affordable housing development easier.

- Urban Renewal Areas can be useful to incentivize housing development in a targeted fashion.

- State programs should adequately size requirements to accommodate smaller, often cash-strapped communities and affordable housing developers.

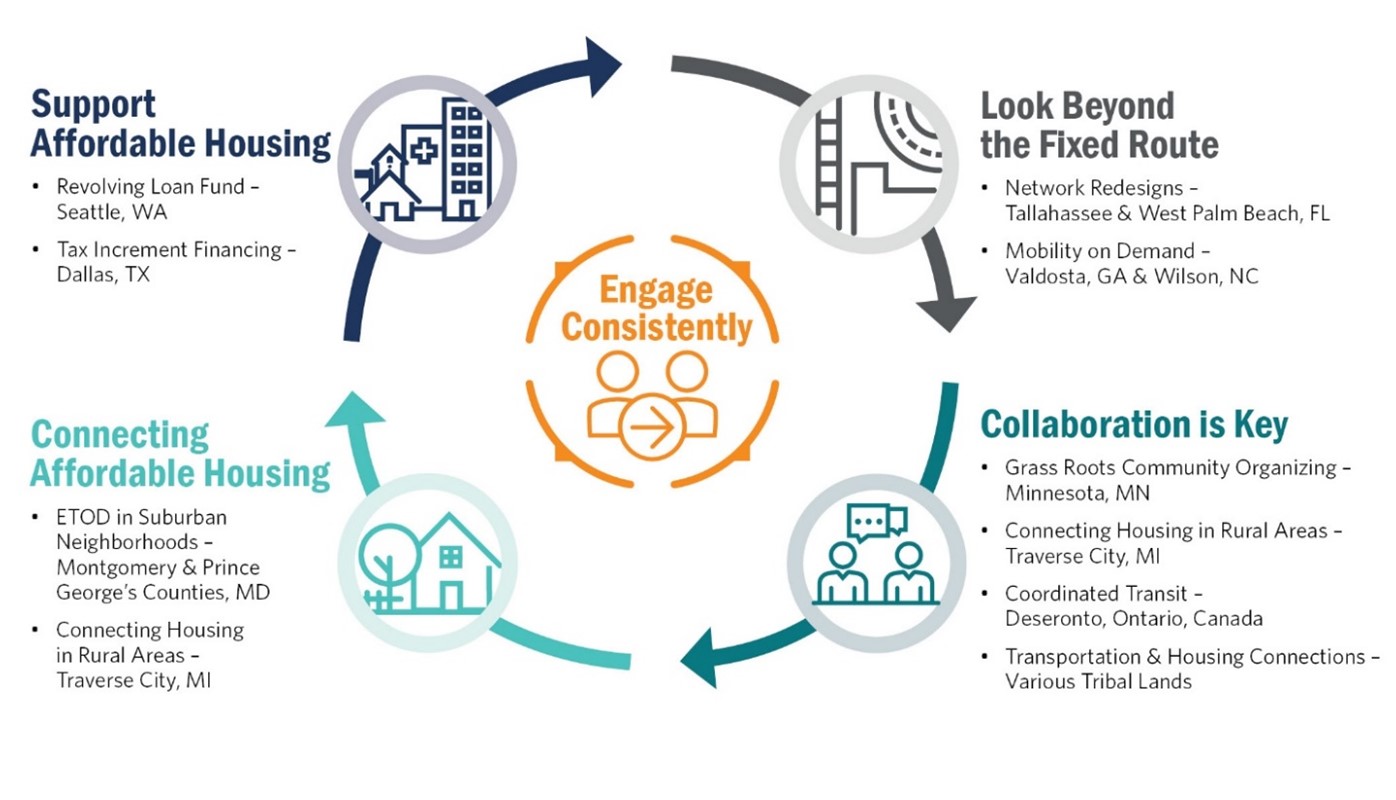

The non-Oregon case studies represent a diverse group of geographic areas ranging from dense urban areas to small cities and sparsely populated rural counties. They include projects - developments, policies, pilot programs - ranging from transit-oriented development and transit route realignments to greater accessibility through strategic stop placement. From these case studies, there are five key findings that can be applied to ODOT, local, regional, and tribal agencies, and transit providers as they implement transit improvements to urban corridors, plan new development in suburban areas, or improve accessibility in rural areas.

- Looking beyond the fixed route is about focusing on the unique social and geographic needs of the community and devising a system that meets those needs. Rural, tribal, and small urban areas have unique challenges requiring a flexible approach to serving residents. The destinations and residents in these areas are spread far apart, which can make fixed-route service challenging to operate. Fixed-route service is when a bus runs along a predetermined, regularly scheduled route with fixed stops along the way. Other types of service, such as Deviated Fixed-Route, Demand Response, and Mobility on Demand service, can bring transit service to where people live as opposed to having people come to a transit stop.

- Collaboration is vital for enhancing transit and housing planning and connections. It allows stakeholders – transit providers, planners, housing advocates, or developers – to assist in creating more convenient connections between transit and housing in partnership. This efficiency occurs in both the public and private sectors. Public agencies, particularly among rural transit providers, can collaborate by coordinating transit operating funds, administrative staff time, and transit routes. Reducing any duplication of service and coordinating how a region is serviced can also result in a more efficient transit service that is easier for riders to use. The collaborative efforts of non-profits and community-based organizations, both with each other and with public agencies, demonstrate the transformative effects working together can have on a community.

- Better Connections Mean More Affordability. The location of housing in relation to transit service plays an important role in increasing the overall affordability of a housing development. For example, service workers along the Oregon coast tend to live further away from their business locations because of high housing costs due to tourism, vacation homes, etc. Low-income communities more often need more affordable transportation options than personal car ownership. If a developer or city chooses to place a housing development on the urban fringe where land is cheaper, but transit service is sparse, then the financial benefits of living there can be eroded by potentially higher household transportation costs.

- There are also differing transit needs in rural and urban/suburban areas. For example, in rural areas or small communities, transit coverage appears to be a more significant need for riders than housing development. In these areas, flexible transit service may be a more feasible method of connecting transit with affordable housing. In urban/suburban areas where robust transit systems may already exist, subsidizing or preserving housing, first mile/last mile connections, and transit stop placement may be more significant to riders.

- Support Those Building the Affordable Housing. There are times when prime locations for both affordable housing and transit come available but, often in areas well-served by transit, land values are so high that development of affordable housing is not feasible. As previously mentioned, siting housing developments adjacent to transit creates a significant amount of benefit for low-income populations as it connects them to more job, education, and social opportunities. By focusing on the location of available land rather than prioritizing the price of land, public agencies and other organizations can support affordable housing developers’ ability to build where the residents would be best served by transit. Developers can be incentivized or supported to build closer to transit services through strategies such as allowing density bonuses, tax benefits, or other financial benefits for the developer.

- Engage Consistently. Public engagement does not end when the project is implemented. Continual engagement with those who use transit services brings better understanding of their needs and ultimately a better designed service and better integration with housing. It is also vitally important that engagement be done through an equity lens. This means acknowledging that not all communities are starting from the same starting point and actively bringing underrepresented voices to the table.

Click the following links to learn more about the Oregon Case Studies and Case Studies Outside Oregon.

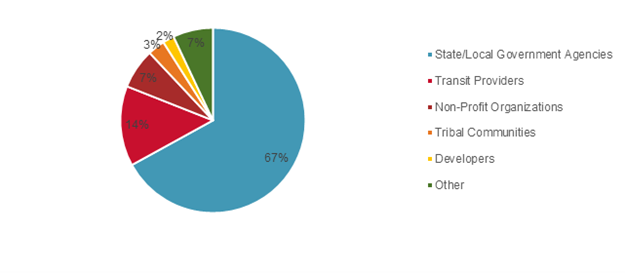

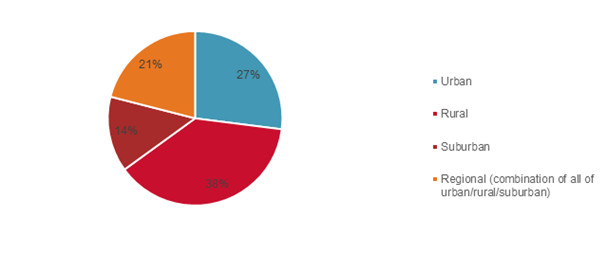

A survey of Oregon stakeholders and practitioners navigating housing and transportation development projects was conducted to identify opportunities, challenges, and tools for better coordination between transit services and housing. The survey included a series of closed and open-ended questions designed to identify barriers and potential solutions to co-locating housing and transit.

Of the more than 600 surveys distributed, 218 responses were received indicating a response rate of around 33 percent. The respondents were comprised of the following organizations and areas served.

Survey respondents indicated some successes with current collaboration efforts between transit and housing stakeholders, such as city or county planners, the general public, state government, and transit providers, followed closely by housing developers and economic development agencies. Some of these collaboration efforts have included co-location activities, such as transportation system planning, land use planning, development review, and the siting of housing developments and transit stops. In addition to these co-location activities, another frequent collaboration effort includes shared funding and partnership opportunities.

Respondents noted differences in providing transit-supportive housing in urban vs. rural areas. Comments on this topic included:

- “Rural areas are tough because the cost per passenger mile is often high due to lack of density and close proximity destinations.”

- “Right now, development of multi-family housing is at the fringes of the urban growth boundary, which generally is difficult to serve due to a lack of street network and the distances from the downtown core.”

Respondents indicated that some of the barriers to developing transit-supportive housing in urban areas include limited land use/availability and safety/accessibility concerns for pedestrians and bicyclists. Respondents in rural areas suggested that transit-supportive housing barriers include long distances to transit stops and infrequency of transit service. Stakeholders from both urban and rural areas also cited funding barriers.

When asked for solutions to transit-supportive housing in urban and rural areas, respondents suggested improving access to transit through enhancing pedestrian and bicycle access, as well as implementing transit-oriented development. Additionally, urban areas recommended parking minimums and restrictions, and rural areas recommended expanding transit service in these areas. About three-quarters of respondents indicated they do not currently offer incentives for transit-supportive housing. Of those that do offer incentives, land use incentives were most popular, followed by grant/funding and housing value incentives.

There are a variety of available opportunities to improve access to transit and housing for people in urban and rural areas, based on the responses provided. To start with, planning and its many implementation tools, including land use, zoning, and transit-oriented development, along with involving transit early in the housing development process could go a long way in establishing improved access. One respondent commented:

- “Including transit at the initial project kickoff meeting is a practice that works but we are rarely invited to the table.”

Other suggested opportunities include improving the frequency and/or effectiveness of transit service in areas with higher housing density, increasing mixed-use development, adding more transit stops, and making transit routes more efficient to serve its residents in these areas. One respondent suggested:

- “Transit has to be a reasonable alternative prior to forcing transit-oriented design or there will be major push back.”

Another popular response was to improve walking and bicycling access to bus stops.

Respondents indicated they would need various types of assistance to be able to develop property they currently own into housing. Respondents indicated they needed the most assistance with funding or subsidies. Other types of assistance needed include incentives, partnerships with developers and/or someone that could spearhead a particular effort, transit-oriented development, supportive zoning, higher density and/or multi-unit housing, affordable housing, and co-locating with jobs/workforce.

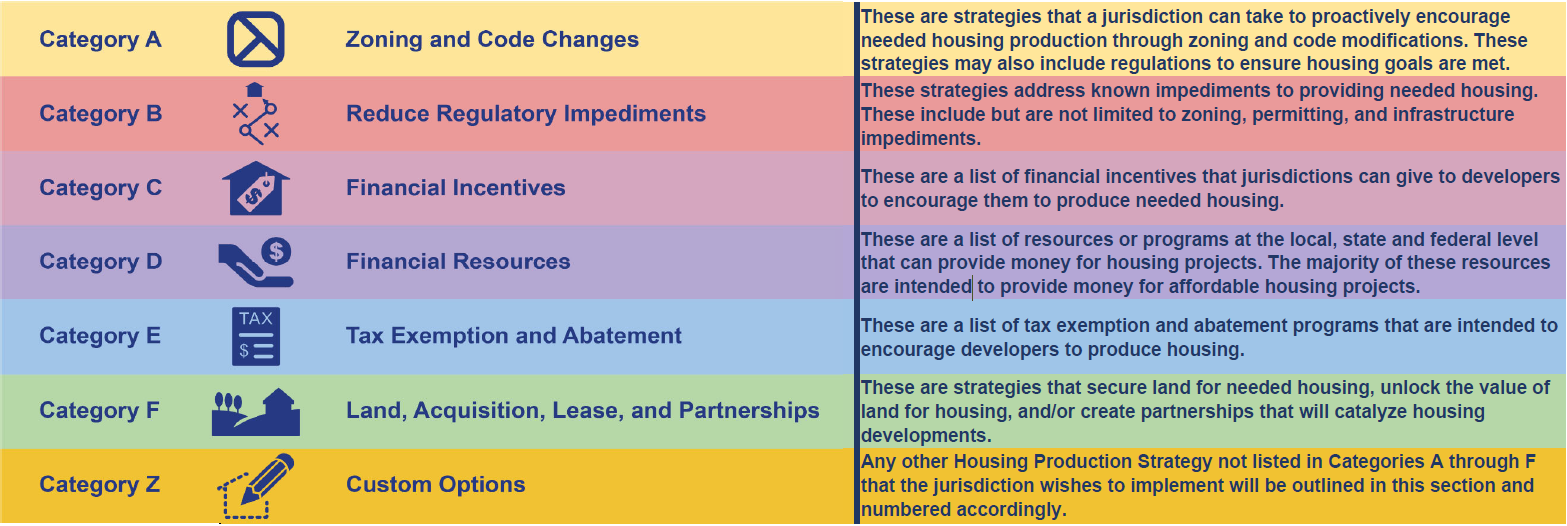

The survey asked about use of tools such as those in the Department of Land Conservation and Development’s new guidance to help jurisdictions comply with new state laws focusing on housing. They include instructions for developing Housing Production Strategies and a list of tools, policies, and actions in seven categories.

About half of the respondents indicated they do not currently use any of the housing strategies or tools. Of those respondents that use the strategies and tools, the most popular are Category A: Zoning and Code Changes, Category B: Reducing Regulatory Impediments, and Category F: Land, Acquisition, Lease, and Partnerships. Respondents also indicated future interest in using Category C: Financial Incentives and Category D: Financial Resources as these tools would most enable them to support or develop affordable housing. When asked the type of support they would need to be able to use the housing strategies and tools, respondents indicated that additional funding, political support, good partnerships, and staffing would be needed.

Three overall themes emerged from the Transit and Housing Survey:

- Respondents want expanded transit in small urban and rural areas. It is easy to coordinate transit and housing in areas with expansive networks of premium transit service (bus rapid transit and/or light rail transit) and high frequency bus service. It is much more challenging to make these connections when a bus only comes once an hour and the coverage is limited. While it is not feasible to provide 15-minute or better transit service in every city or rural community in the state, further funding for transit in rural and small urban areas is a highly requested item from the respondents. Ensuring access to a variety of transit services (e.g., fixed route, demand response, or Mobility on Demand) throughout the state can help people meet life-sustaining activities and make connections to intercity transit service to access services in other parts of the state.

- Respondents also support enhanced coordination efforts between housing and transit to increase density and/or development along existing transit routes. The availability of transit does not necessarily mean there is a sufficient level of coordination between transit providers, developers, and planning and zoning agencies. This sometimes results in new affordable, dense developments being built in areas where there is no transit service, or the route/service is limited and ill-prepared to handle the influx of potential customers. In addition to strengthening transit around existing housing developments or high-density areas, developers of new affordable and/or dense housing can also be incentivized to work with transit providers and place these developments where there is sufficient transit capacity to support them. This can be done through, as mentioned by the respondents, relaxing parking requirements in targeted areas, promoting transit-oriented developments, allowing density bonuses (zoning provisions to allow more dwelling units to be built in a given area), or providing additional funding (grants or loans) for housing development projects that include transit in their plans.

- There is a strong need for providing first mile/last mile connections. Even if transit is available to support housing, access to the transit network can still be a barrier, limiting its effectiveness. Numerous respondents highlighted the need to provide better first mile/last mile connections to help access those areas where it is not effective to extend the transit route. This is accomplished through improving bicycle and pedestrian connections, such as sidewalk and crosswalk infrastructure, between housing and transit along with implementing micromobility programs (e.g., e-scooter, bike-sharing) where feasible.

To learn more about the Transit and Housing Survey, click here.

The study can help guide public investment and lead to denser developments along bus, streetcar, and/or rail lines. It can help implement national and statewide emissions initiatives, such as the Climate-Friendly and Equitable Communities Program, to help meet climate change targets. Most importantly, this project provides recommendations and strategies to help make Oregon a better, more affordable place to live.

In the toolkit, transit providers, state agencies, and local, regional, and tribal agencies and their leaders and decision makers can explore various tools, actions, and strategies identified throughout the study. The toolkit will show them along with attributes such as level of effort, what kind of agency likely has authority to implement, etc.

The final report collects and summarizes the lessons of all the mini-studies that built this Oregon Transit and Housing Study.

This study consisted of a series of smaller studies as described throughout this online open house, that lead up to the final report and toolkit. These interim reports have in-depth information for public agency staff and stakeholders to consider. See all these products listed below on the project website.

Thank you for taking time to explore these study results, and thank you also to all who contributed to this study. Please feel free to share the products with others who may be interested.